An Audience with . . .

On 25th February, 2021, Kevin was Nikki Gamble’s guest on the brilliant series ‘An Audience With. . . ‘

Bruder und Schwester wie Wort und Bild?

A fabulous article written about Kevin’s collaborations with artists and illustrators. Published by Intellect

Go North, Young Man

North Norfolk Living – 13th October 2020

As author Kevin Crossley-Holland approaches 80, he tells Alison Huntley about his career’s great turning point and his undimmed creativity

The poet W H Auden effectively launched the award-winning writing career of North Norfolk author Kevin Crossley-Holland with two words – “look north”.

Auden had read the young Crossley-Holland’s translation of Beowulf and knew of his fascination with myth and legend – he also knew that there was more untapped inspiration to be found in Scandinavia.

Backstage at the 70s ITV arts show Aquarius, the two had a conversation. “He said “Look north – there are so many northern stories and sagas and you’re a northern creature”,” says Kevin.

“So I did look north! It was 1978 and I gave up my job in publishing and took myself and my two children off camping in Iceland.”

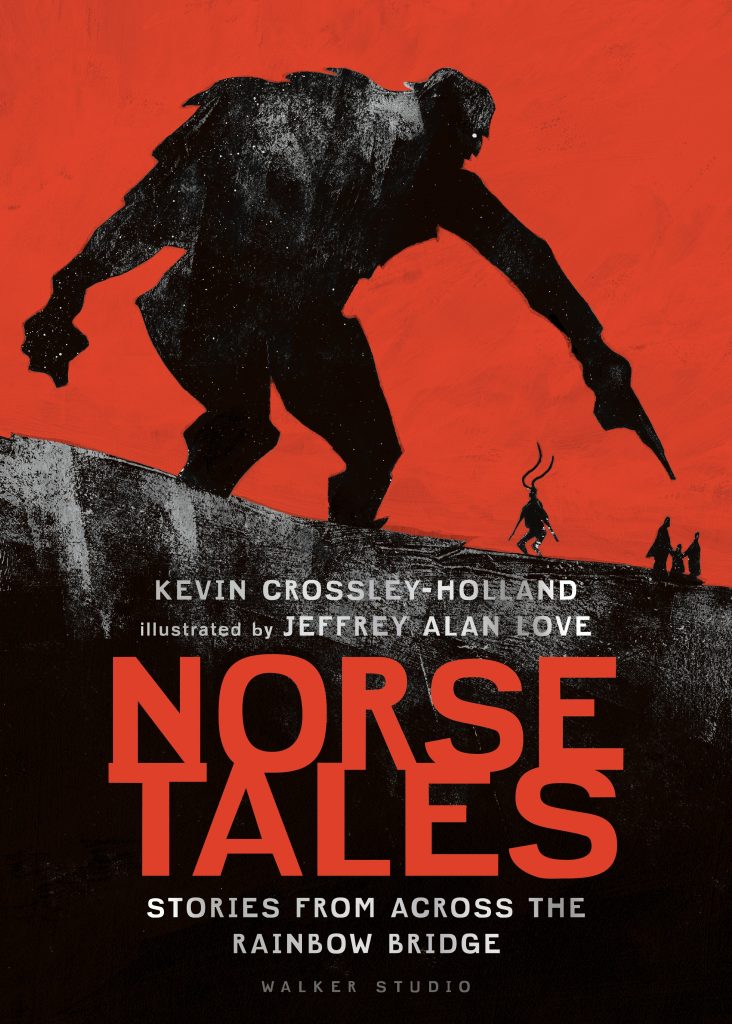

The journey had begun. Decades later, his reworkings of Scandinavian legends are as successful as ever – September saw the publication of Norse Tales, five thrilling stories for children, beautifully illustrated by Jeffrey Alan Love.

“With Norse myths, there’s very little compassion or kindness or uncomplicated love. They were vigorous, the Vikings, often exuberant, essentially masculine, extraordinarily brave, even reckless. There’s a ruthlessness which children adore.”

The Scandinavian works are just part of a prodigious output that includes Arthurian stories and Norfolk tales, amongst others. And at 79, Kevin is as busy as ever. He has just started the third in his Viking Sagas trilogy. Not even lockdown slowed Kevin’s creative juices. He came up with ‘Belonging’ – 20 lockdown poems based on his five local Burnham parishes. These are “playful” poems with a “lightness of touch,” says Kevin.

“They have to do with times past and present, but they are oriented to people who don’t usually read poetry.”

And he’s just completed a new book, Arthur the Always King, which will be illustrated by Chris Riddell.

Contrary to appearances, Kevin insists “I doubt my creative energies are what they have been. I need a rest after lunch now.” Even so, he puts in three- or four-hours’ work in the morning and works again in the evening. “We eat late.”

Not even a stroke five years ago slowed his creative output for long, although it did temporarily rob him of speech. “But a wonderful speech therapist worked with me for more than a year. Coming back to public speaking was quite difficult. And in the evening when I’m tired, I find myself jumbling up words and I hate that.”

Lockdown had its benefits – cancelled events and travelling meant more time on his hands. Kevin was also heartened that it encouraged more community spirit and kindness. Unfortunately, lockdown also highlighted his struggle with his bête noire – technology.

“I’m prehistoric and I find it really difficult, almost impossible. With help from my PA, I did an online talk with Joanne Harris and Ben Okri for the Yorkshire Festival of Stories. There was an audience of 300 but there’s no feedback, no ripples of laughter. It’s exacting and wearisome.”

No plans have been made yet to celebrate his milestone 80th birthday next February and Kevin seems unsure whether it’s worth celebrating.

“Looking at slightly doddering contemporaries, I find it not very pleasing to find myself on the doorstep of 80. We are all a bit older than we think we are.

“What can you do? You can’t plan anything. It looks like this COVID situation will go on a long time yet. I’m not really a party type anyway.”

Let’s hope that after an award-winning career as author, poet, playwright, translator and opera librettist, he’ll find someway of celebrating.

Not the retiring type!

At 76, local poet and children’s author Kevin Crossley-Holland is busier than ever. Amanda Loose tries to keep up

“I’ve always had a lot of different balls in the air at the same time and this last year perhaps more than ever,” says Kevin. “I am trying to cut down on invitations, but I’m not doing very well at it. I am collaborating with more artists in other disciplines than ever before. I can’t imagine retiring – being curious, involved with a range of things generates its own energy.”

And energy is something which Kevin seems to have in abundance. The beginning of November saw the publication of his Norse Myths: Tales of Odin, Thor and Loki for children, with illustrations by Jeffrey Alan Love. Meanwhile, Radio 4 wants to make a 30-minute programme with him about the tides on the Staithe at Burnham Overy over 24-hours; David Cohen wants to make a film about Kevin based on the moored man from his poems, to premiere at the Oxford Literary Festival next March.

Not bad for starters, but hot on the heels of his collaboration with composer Cecilia McDowall on As Each Leaf Dances, written at the invitation of Barnardo’s for the service of thanksgiving to commemorate its 150th anniversary at St Paul’s Cathedral last year, Kevin and Cecilia have just embarked on a new project together.

Their commission for the National Children’s Choir will focus on children in conflict, with the story of cerebral palsy sufferer, Nujeen Mustafa and her journey with her sister from Syria to Germany at its heart.

Closer to home, Kevin was involved with the beLong education project which ran alongside the Richard Long exhibition at Houghton Hall this year, writing poems for key stage 2 and 3 pupils. And his cycle of poems about Sea Henge at Holme will be appearing in an updated version of The Stones Remain: Megalithic Sites of Britain with photography by Andrew Rafferty, and text by Kevin.

“I have Valkyries on either side of me, my wife and PA, suggesting I remember that the answer is no. I think a lot has to do with just plain curiosity. Everything is connected to so many other things. Curiosity is the thing which drives me, coupled with a sense of wonder really.

“In old age you forget things more, you treasure friends, family, especially grandchildren, and have a keen sense that you need to prioritise. Prioritising is beginning to make its mark on me.

“You have to begin to say this is what your body is saying. I always resisted this and pressed on regardless. Now I quite often rest in the afternoons. There is a weariness, I am 76 which seems so absurd. There’s a growing disappointment at how other people see you and how old you feel. But you must be a little more cautious.”

As busy as he is, North Norfolk remains home and a continuous thread throughout his work. “I never regretted for one moment living here. With my grandchildren, there have now been five generations of Crossley-Hollands coming here.”

Child literacy is hugely important to Kevin, who has just come to the end of five years as President of the School Library Association, and is now a patron. “My wife Linda does reading at the school each week here, part of a frankly splendid group who give a couple of hours each week to work on literacy.”

This Carnegie Medal-winning author’s extensive backlist of works for children has surely inspired many a young reader. Indeed, Short and Short Too, his sequences of short stories printed over a double page have been a hit with schools, with the former reprinted 35 times.

“The act of storytelling itself is so crucial. In an age besotted with the visual, we need our imaginations fired, and they are best fired by a story told with an ear to the music of language.”

Young (and older readers) will be delighted to hear that Walker is re-issuing his British Folk Tales next year, and that Kevin is “re-brewing” his children’s book on the 1953 flood. I’m just not sure I can keep up!

Amanda Loose, North Norfolk Living

Article written for the Letterpress Project: Bookshop Memories

Hodges Figgis, Dublin, 1960-2

The first poet who set me on fire was an Irish word-magician.

How I treasure the Macmillan hardback edition of his collected poems in its magenta binding, given to me, complete with inscription and yellow friesia (still there and still yellow) by Grania, the girl I’d met the week before during our first days up at Oxford.

So when I had the opportunity to travel to Dublin, all expenses paid, as part of my college tennis team (sometimes my partner was the West Indian poet Mervyn Morris, who played at Wimbledon), and with it the chance of visiting Ireland’s oldest bookshop, Hodges Figgis, it was like the promise of entering Paradise. All the more so because, as my mother never failed to remind me, I was one-eighth Irish, and could claim descent from the Keoghs and Sweeneys and Vere de Veres.

Fortified by pints of Guinness in the pubs where the word-magician had spent hours, and after time spent gazing at Georgian houses he had lived in or visited, I stepped across the threshold.

Founded in 1768, Hodges Figgis was a shop that looked very much smaller from the outside than it was on the inside. Akin to Blackwell’s in Oxford today. At once I was aware that this was a place altogether apart. It was quiet. You were not discouraged from talking to other browsers (or to yourself) but if you did, you spoke to them quietly. It was a sort-of secular sanctuary, wise with all the words and stories and poems within it, wise with the aura of all the great writers and other artists who had patronised and loved it.

The stock of books was obviously arranged, but lightly so, and according to principles that might escape you until a second or third visit. Not only that, many of the books on the shelves were brand-new, but they stood cheek-by-jowl with second hand books and books long out-of-print. Piles of rather tatty literary magazines were perched rather precariously on stools. While behind gleaming glass lived the precious limited editions…

Here and there, quite elderly acolytes, dressed in grey baggy suits, were arranging and rearranging books, doubtless keeping an eye on potential customers, and offering advice when asked without inflicting too much of it.

In Hodges Figgis, I discovered 19th century magazines at knockdown prices containing the first printing of well known poems by my word-magician. Excitedly I drew them to the attention of one or another of the acolytes who then immediately withdrew them… How naive I was!

But there, too, during three spring tennis tour in successive years, I bought for £2.50 each almost a dozen copies of Elizabeth Yeats’ beautiful, hand-printed Cuala Press editions of poems, prose and paintings by her brothers William and Jack, Rabindranath Tagore, Patrick Kavanagh and many more. And then, back in Oxford, I was able to come out all square by selling one at £5 for each one I kept.

After Oxford (a poet’s third, for the record!), I found a job as number three in the publicity department with the publishing House of Macmillan, home not only to W B Yeats but of so many of his Anglo-Irish contemporaries – AE and James Stephens, Lady Gregory and Padraic Colum and J M Synge.

Before I knew it, I was corresponding with Sean O’Casey… his erratically-typed letters hopped all over the page. As a young editor, I went on raiding parties to Ireland and made friends with Eavan Boland and Michael Longley and many another, and very proudly published them. Apt to take so much for granted, like many another confident young man, I was still awed and seriously excited to be able to meet George Yeats – and I threw at her feet dozens and dozens of red roses. Later, she gave me permission to make a selection for children from W. B.’s work, the first of its kind, Running to Paradise.

Ah! How one thing led so quickly to another – my appointment by the leading Anglo-Irish literary critic A N Jeffares as Gregory Fellow in Poetry at Leeds University (1969 – 71); friendship with the literary editor of the Irish Times, Terence de Vere White; making a pilgrimage to Glendalough; visiting Inishmore and meeting Maggie Dirrane, star of Robert Flaherty’s Man of Aran.

What I’m saying is that the best of bookshops not only nourish literary curiosity of all kinds but can have a seminal influence on one’s life – in my case, on my writing, publishing and social life.

I’ve taught courses in the aisles of an American bookshop (the now defunct Hungry Mind in St. Paul) to students astonished to find the poets we were discussing were alive and kicking and looking down at us from the shelves – Allen Ginsberg and Galway Kinnell and Gary Snyder and Rita Dove. I used to lounge for hours in deep spring-less armchairs in Blackwells and read what I couldn’t afford to buy. In Cracow recently, I was thrilled to see tables displaying holographs by Milosz and Szymborska…

Yes, there are still some booksellers and bookshops worth the name, not least those catering for specialised interests – and certainly not least those involved in the crucial work of igniting in children a passion for books. ‘Reading for Pleasure’ is such an anodyne, forgettable catchphrase – we should be talking about flames and fierce joy and setting fire… Which is where, with W B Yeats, I began.

Kevin Crossley-Holland

Interview for ‘The History Girls’:

A visit from Kevin Crossley-Holland

This is a big day here – our first ever “History Boy” posting for us! And it’s Kevin Crossley-Holland, which is a bit like having a visit from, oh, I don’t know, Odin perhaps. (Though his favourite is a different deity) We subjected him to quite a grilling and the results, below, speak for themselves.

Thank you so much, History Girls, for according me the honour of being your first ‘history boy’, and for your searching questions. Here goes!

Could you expand on why the story of ‘The Green Children’ has haunted you for so long?

Imagine an eager, anxious boy lying on the top half of a bunk bed. His sister, three years younger than he is, lies on the bottom. Their father sits beside the bunk, eyes closed, and sings-and-says folk tales, accompanying himself on his Welsh harp.

That’s when I first heard the story of the two green children who were found near the Suffolk village of Woolpit at the end of the 12th century – so says Ralph, abbot of the monastery at Coggeshall (where, traditionally, everyone is a fool!)

At once, I identified with this plangent tale of brother and sister who long to belong and, like all of us at one time or another in our lives, feel lost, feel like outsiders. In a way, they stand for all the refugees, all the homeless, all the people in camps, all the dispossessed, who walk across our Middle Earth.

Later, by co-incidence (in its proper sense), my family moved to a village close to Woolpit in Suffolk… Then Nicola Lefanu and I made a children’s opera (for King’s Lynn Festival with the ENO Baylis Programme) from the story, involving literally hundreds of children. Later yet, I rewrote the tale from the viewpoint of the green girl… And at the last, this most haunting of tales will still be with me.

Several of you have invited me to describe how I research, plan and generally cogitate before writing, and about my writing process.

As I’ve described in my memoir of childhood, I wasn’t much of a reader as a boy, though I reread Our Island Story until it fell apart, but I absolutely loved my ‘museum’, and with the help of my father learned to investigate and catalogue the items in it (fossils, Roman coins, a lovely Anglo-Saxon burial urn, and my astounding Saracen shield – not to mention my hoard of bun pennies on which I wasted a great deal of time, forever trying to buff them up with Duraglit!)

Always neat and well organised, I wept copiously when I returned from our first holiday abroad (I was six) to find that the family to whom we’d lent our little cottage in the Chilterns had raided and ransacked my toy cupboard.

I bring the same method, I think, to writing historical fiction. What do I need to find out? How am I going to find out about it? What do I have to do to convince myself and thus my readers that we’re on reasonably safe ground?

Well, I guess my answers will be the same as yours. I read and read – original sources most certainly (albeit in translation), serious interpretations of the period in question, and provocative books (often by French scholars) that cast a wider net – Duby on Love and Marriage in the Middle Ages, Le Goff on The Medieval Imagination, Eco on Art and Beauty in the Middle Ages. And all the while my wonderful PA Twiggy turns up lots of rapid-fire information from the internet.

I look at medieval art, I listen to lots of medieval music, I trawl museums and, in so far as is possible, I spend time in places where my books are set.

Thus I regularly returned to the Marches while writing the first book in my Arthur trilogy, and travelled to Zadar (once Zara) in Croatia, the setting for most of the third book in the trilogy, where the Fourth Crusade Christians laid siege to and devastated a Christian city.

At the same time, I’m beginning to plan the book – its thrust – the ideas I want to explore, the tough issues, the conflicts that drive it along – the characters, possible scenes, details… Ah! You know how it is. I do some of this work on giant spread sheets, but most on handwritten A4 sheets that soon build into piles. So, for my last book: Viking Women, Boat-building, Names, Merchandise, Weaponsmiths, Jewellery, Ladoga, Harald Sigurdsson, Rus, Black Sea, and so forth. Before long, these piles become tottering edifices.

I write entirely by hand with my old Waterman pen in the most lovely cloth-bound dummies given to me by publisher friends (yes, academic books still sometimes begin with dummies!). My writing may look neat, even attractive, but it’s not easy to read, I gather. And when I’m signing books, children and parents sometimes hesitantly come back to ask me to decipher a word. Heigh-ho!

I work on the principle that a working day deteriorates and by and large aim to think, dream, write, revise from about 8.30 or 9.00 until 1.30 or 2.00. How on earth author wives and mothers who often have to fit in so much bitty-piecy work in and around the home, are able to write as well, fills me with astonishment and admiration. My powers of concentration are considerable, but for me it’s a matter of momentum, and I doubt whether I could write in a pick-it-up and put-it-down sort of way.

I begin most days by revising the previous day’s work. It’s almost like tuning an instrument and practising scales: ensuring that my ear is true and that I’m right on the ball. I read my text out loud, or under my breath, and always use a second colour to revise the previous day’s work (and a third when I revisit that) so that I can see at a glance how things are coming on.

Twiggy types my complete revised manuscript and I then put a novel through three or four more fierce revises – quite apart from structural alterations (which I hate), maybe eight or ten small changes per page – that’s to say several thousand small corrections each time round. At the same time, my wife Linda is also working on a draft, brandishing a blue pencil, asking questions and offering invaluable comments about the dynamic, pace, text – everything. In another incarnation, she would have been a wonderful editor. And of course the decline of the publishing editor is a grievous matter – one for another day.

As we know, there’s nothing magic about using language really well and children can learn to do so: that’s why many of us run writing workshops. I think it’s essential that those teachers involved with creative writing classes should also write themselves from time to time.

Last autumn, I was on the road too much, and overdid it (some forty talks, workshops, festival events and so on) but in round terms a new novel may take me about eighteen months. With my forthcoming Presidency of the School Library Association, though, I suspect the next one may take me rather longer.

I reckon that 40% of my writing time is given to research and planning, 25% to first draft, and 35% to revision. Like an hourglass, almost.

How do I ‘approach deciding on the level of language’ I use in my children’s books?

True, I did write a couple of historical novels in my early twenties, but to all intents and purposes The Seeing Stone was my first novel. I was fifty-eight when I wrote it. And I really didn’t know how to write it, or whether what I was writing was any good. I showed it to my wonderful long term editor Judith Elliott after I’d written 80 pages, and then again when I written another 80… At the heart of my uncertainty were the crucial questions of viewpoint and voice, and pace, and yet I cannot truly claim that I spent hours agonising over them – Arthur’s voice just welled up, like so many of the book’s incidents, the voice of an eager, anxious, active, articulate, imaginative, impressionable young boy of 12 not at all unlike that of his author when he was a boy.

During the 90s, I’d written two libretti, and that discipline taught me several new skills: getting people on and off stage at speed, seeing a relationship or event from different viewpoints, employing nothing but dialogue and internal monologue; altering the texture of the language (intensified for an aria, more relaxed for the recitative that carries the action along). To some extent, I applied these techniques to The Seeing Stone. Thus, many of the very short chapters are akin to arias – written in somewhat poetic prose as Arthur delves into his own thoughts and feelings. More of them, and one might die of indigestion. But as things stand, they seem to work quite well.

As a poet, I’m aware that every syllable counts, and every silence too. The music of language is part of our meaning, and we must harness it, and have it help us to sing.

This blog post(not that I’ve ever written one before) is surely getting too long. So I’ll turn to the Vikings and their myths and Bracelet of Bones – subject of many of your questions.

It was Wystan Auden who encouraged me to look north to the world of Icelandic sagas, eddaic poems, Germanic heroic legends, and to consider retelling the Norse myths.

Much the most complete and coherent contemporary versions of the myths were written by the 12-13th century Icelander, Snorri Sturluson, and when I read them, I was aware of the landscape between the lines, as it were – the world of ice and fire that Snorri’s original audience must have taken for granted. And it seemed to me essential that any writer thinking of retelling the myths should fully engage with it.

So that’s what I did. With all the zeal of the convert, and to much shaking of heads from family and friends, I threw up my job as editorial director of Victor Gollancz, and went camping in Iceland with my two young sons. I was 36.

Western art has been so much influenced by Mediterranean cultures, and by the Renaissance – and so relatively little by, let’s say, the bracing floes of the North Sea and the Baltic. William Morris and several of the pre-Raphaelites, yes. Wagner, yes. Tolkien, yes. T. H. White, I suppose. Auden himself. Who else – of the first water? Very soon one’s having to scrape around. And yet, we British are of the north-west European world. It’s in our bloodstream, our nervous system, our language, our laws, our landscape, our stories… And so, for obvious and subtle reasons, the myths, legends and sagas are likely to speak to us.

The Norse myths, racy and witty and ice-bright, with sharply differentiated characters, are by no means as subtle and developed as their Greek counterparts. And yet we find in them, and in their nine worlds under the great, suffering guardian tree, Yggdrasill, the full repertoire of human dream and experience. Here are all our own high hopes, ambitions, fears, loves, passions, jealousies, rivalries, conflicts (often with ourselves), sacrifices and self-sacrifices, our wit and lust and greed, and here too our longing for some deeper order and meaning. What more can one ask? Isn’t this precisely why the Norse myths are not only still popular but – as we say in East Anglia – coming again?

I suppose my favourite deity is Thor, the maintainer of law and order, because he’s a likeable blockhead, trustworthy, easily duped, quick tempered but also ready to laugh at himself. But Loki, son of two giants and yet companion to the gods, is the most interesting character in the myths because of his ambiguity, and his own decline and fall – from laughable trickster to murderous enemy of innocence and virtue. (No, I’ve never sent the Loki stone at Kirkby Stephen but will make a point of doing so.) Loki is the agent of change in the myths, and the one in which he and Thor travel with two human companions to the world of giants is vivid, entertaining and scary, but my favourite myth is ‘The Death of Balder’. The loyalty, ferocity, pathos and sheer gravity of this tale, embracing as it does all creation, makes it one of the greatest of all stories, anywhere.

After writing the Norse myths, more than 30 years ago, I thought that was that. But as I described in the foreword to Bracelet of Bones, my wife’s and my discovery of Viking runes in Hagia Sophia (in Istanbul) was the springboard for a novel in which a girl, Solveig, follows her father in 1035 from Norway through the Baltic, Russia, Ukraine and the Black Sea to the city the Vikings called Miklagard.

Solveig’s head is full of the myths she has grown up with, as well as the new Christian teaching that has recently reached Norway. She keeps returning to values embodied in each of them, as well as learning about Islam when she accompanies her father and Harald Sigurdsson to Sicily in the second of my Viking sagas, Scramasax. As in The King of the Middle March and Gatty’s Tale, I find myself drawn to crossing-places and their ferment: places between cultures, belief systems, between land and sea, between childhood and adulthood, innocence and experience, actuality and imagination.

As we know from contemporary sources and modern historians, the role of women in Viking society was wide-ranging and potent. I see that one of my A4 pages lists them as household managers (i.e. running largely self-reliant farmsteads), loyal to a fault, inciters of feuds to protect family honour and yet also arbiters in community disputes, scapegoats, praise-subjects, beloved, beautiful and dangerous, feared for their sexual and magical powers. What is missing, yes, is much talk of Viking women as mothers!

I decided that I wanted to find out how a Viking girl might fare on a great adventure without being disguised as a boy. In Scramasax, I’ve ventured further and planted poor Solveig in an army of men. One thousand men; one young woman. Solveig comes face to face with their actions, their values. Will she ever be able to reconcile them with her own?

In selecting a girl as my main character, I’m also accepting, I suppose, that on the whole I find girls more interesting than boys, women more interesting then men. And certainly during the last few years, when my daughters have fallen in love and the elder has married, I’ve been conscious of how the role of father changes. No longer is he the beloved! So you could argue that Bracelet of Bones and Scramasax are novels about a girl defining her changing relationship with her father (and to men) while her author was of necessity redefining his relationship to his daughters.

And so, to end with, a few little quick replies:

Is Gatty my ‘favourite imagined character?

Yes, actually. Though she began life as a boy: Sneezer. After writing 50 pages she had a sex-change in the mind of her author, and he went back to square one. I’m rather partial to my Annie, too, in Storm and Waterslain Angels.

If I could time travel and witness one historical event, what would it be?

Maybe the first recitation of (the first part of) Beowulf, whenever and wherever it took place – perhaps at the court of the Wuffings in Suffolk in the seventh century. Of course my eyes would be out on stalks, and all my senses in play, but I reckon I’d be able to understand much of the language too. Or else – well, what about the stunning pagan-Christian Sutton Hoo ship burial, and all the rituals enacted at it? A crossing-place, if ever there was one.

What am I most proud of?

Wasting very little time. My powers of concentration. Trying to return the kindnesses done to me when I was beginning to write – by enthusing, and enabling others. For all its rivalries and spats, the world of writers (and more especially of children’s writers) is collegiate.

Do I have rules/views that affect how I retell a story?

Certainly. I laid them in out in my talk ‘Different – but oh! how like’ published in the Society of Storytelling Oracle series.

And if you…. or you… look into the seeing stone, you’ll see all you can and so must write. Look back (as we historical novelists do). Look forward. Remember the parable of the talents. With all my head and heart, I wish you success in revealing the ‘then and now’ that makes the study of history so fascinating, and the deep and lasting satisfaction of a serious undertaking, well done.

Thanks so much, Kevin, for all your wonderful answers, and your final gift to us and our readers. Can’t wait to read Scramasax!